Mycenaean Greece

Archaeologist Jorrit Kelder is an expert and scholar in the ancient Aegean world and his book, The Kingdom of Mycenae, provides valuable insight into Mycenaean Greek society as well as the wider ancient Mediterranean world from 1750-1050BC. It is a thoroughly enjoyable read and it brings to life a fascinating chapter of Greek ancient history.

The Kingdom of Mycenae discusses many topics including the political organization and leadership of Mycenaean Greece at the highest levels of society. In comparison with the detailed knowledge of later Greek polities and their officials, Mycenaean officials’ titles are less precisely understood and often without agreed-upon etymologies. This even includes the titles of two men at the apex of Mycenaean society, the 𐀷𐀙𐀏 (Wa-na-ka) or Wanax and the 𐀨𐀷𐀐𐀲 (ra-wa-ke-ta) or Lawagetas.

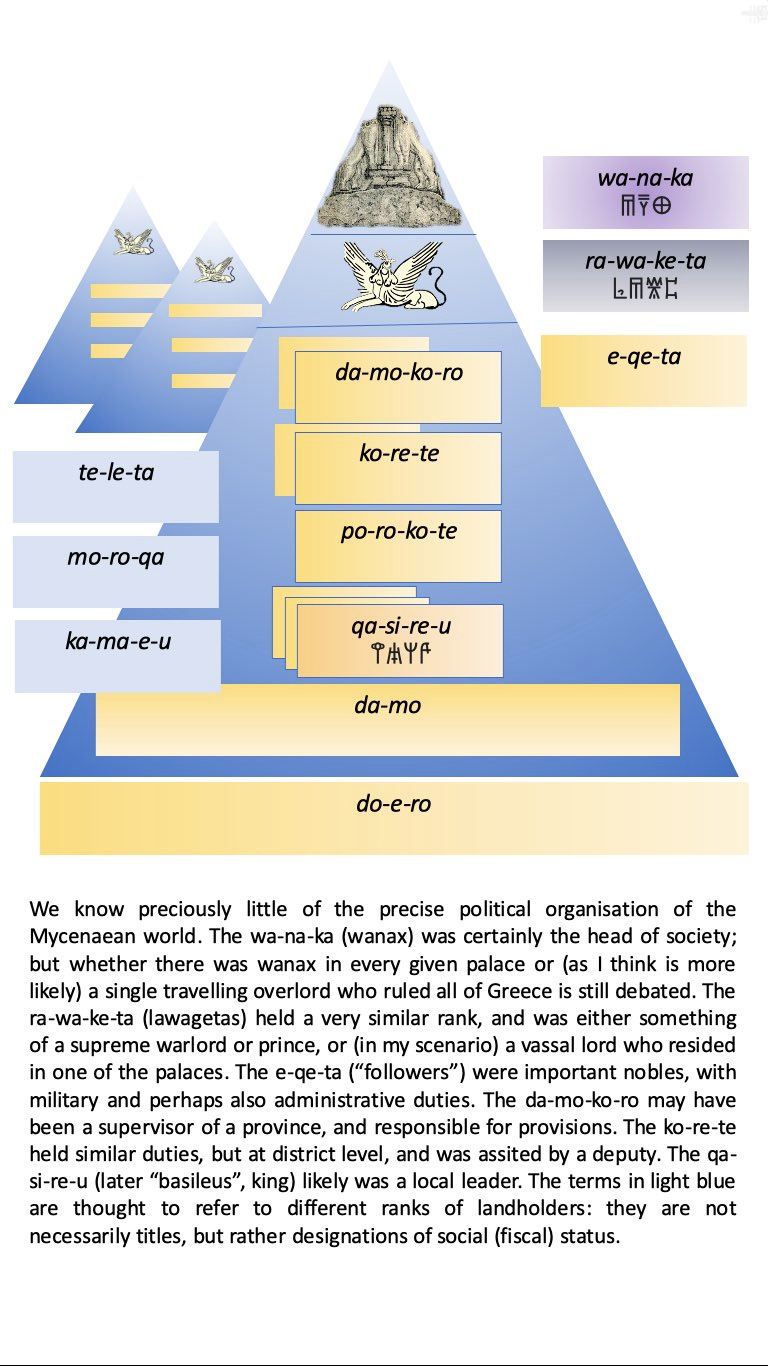

Kelder’s concise illustration below shows the Mycenaean officials and groups, and also has an informative caption:

Linear B and the title 𐀨𐀷𐀐𐀲 (ra-wa-ke-ta) Lawagetas

The Mycenaean titles are written in the syllabic script named Linear B and it predates the Greek alphabet by several centuries. There are challenges with reading Linear B signs and they require interpretation.

The Mycenaean title 𐀨𐀷𐀐𐀲 (ra-wa-ke-ta) is interpreted as Lāwāgetās, an official Kelder describes as a kind of prince who was second only to the Wanax. Both men performed martial, religious, and civic duties. Kelder notes the lack of evidence for the current consensus for the etymology of 𐀨𐀷 *Lawa meaning “army” and therefore Lawagetas as simply an “army leader”:

Similarly, attempts to deduce the function of the lawagetas in Mycenaean society on etymological grounds appear to be problematic. Of these attempts, the one most often heard is that the lawagetas was the military commander of the typical Mycenaean state, a concept based on the assumption that laos refers to the population able to carry weapons, i.e., the army. As noted, this is an assumption and there is, in fact, no direct evidence to support it.

The root *Lawa is speculated to originate from a different root in the next section.

𐀨𐀷 Lawa

The McGovern et al (2013) paper indicated that wine from southern Europe could have been in Scandinavia as early as 1100BC. That means Proto-Germanic tribes in Scandinavia imported Mediterranean wine and adopted its name as *wīną from Italic *wīnom or Hellenic *wóinā at the twilight of the Mycenaean era. If the /w/ in English wine is a fossilized testimony to early Mediterranean to Germanic word borrowings when Mediterranean /w/ still existed, then the /w/ in Dutch leeuw “lion” and German Löwe “lion” could be too.

Mycenaean Greek 𐀨𐀷 *Lawa in 𐀨𐀷𐀐𐀲 Lawagetas is proposed to mean LION.

Two relevant etymology notes complement the proposed idea that /w/ was present in Mediterranean “lion” words at the earliest stage:

On Gothic 𐌻𐌰𐌹𐍅𐌰 (laiwa) “lion”: “This [Gothic *laiwa] does not look like the regular outcome expected from a direct borrowing of [Latin] leō.”

On Proto-Semitic labiʔ “lion” and its borrowing: “Gamkrelidze & Ivanov argue on the possibility of borrowing into Proto-Indo-European *lewo-, though it remains debatable.”

During the post-Mycenaean transitional period 1100-800BC, these notes imply that *Lawa evolved in the Mediterranean to Gamkrelidze & Ivanov’s proposed stem *lewo-. It was this iteration that Germanic language speakers imported as *lēwō and 𐌻𐌰𐌹𐍅𐌰 (laiwa) along with other Mediterranean words with /w/ like wīną “wine.”

A half century later, Ancient Greeks were using “lion” in the initial part of royal names like the famous Spartan Kings named Λεωνίδας (Leonidas) “son of a lion” who claimed descent from Heracles, the Greek most associated with lions.

Heracles also shares a connection with the next root.

𐀐𐀲 Ge-ta “Leader” or “Founder”

These two syllables are understood as “leader” or “founder” in the consensus etymology, and this meaning best matches the second two Linear B signs of Lawagetas, 𐀐𐀲 (ge-ta) to the Doric Greek spelling of γέτας (gétas). This root is also found within the title ἀρχᾱγέτας (arkhāgétas) meaning “leader, founder, prince, chief, governor” and it was a title for Greek gods and heroes like Heracles:

[The ἀρχᾱγέτας (arkhāgétas) was] primarily… a title for Greek gods and heroes that typically indicated one who was an originator or ancestor, especially of new colonies or settlements. This could be seen most commonly with Apollo, but sometimes also with Heracles and the heroes of the demes of Attica, and the Thracian horseman.[1]

The complete title 𐀨𐀷𐀐𐀲 Lawagetas means “Lion Leader.”

Mycenaean Olympians

Many scholars have proposed that famous stories within Greek mythology take inspiration from true events and real people during the Mycenaean period. Tales of Zeus, King of the Gods, may have been inspired by the exploits of one or more Mycenaean Wanax. Zeus’ consort, Hera, had an epithet of Ανασσα (Anassa) meaning “Queen” from the feminine form of Wanax. Heracles was the lion-skinned son of Zeus and he would have been equivalent to a princely 𐀨𐀷𐀐𐀲 Lawagetas. His pedigree and heroic deeds made him a model “Lion Leader” prince.

Heracles, the ultimate Lawagetas

Heracles’ timeless princely activities are recorded in his famous Twelve Labors: killing or capturing dangerous game, raiding livestock, stealing treasures, and engaging in single combat. His first Labor was single combat with the Nemean Lion, a euphemism for the Lawagetas of Nemea who was well-protected by his heavy golden-bronze armor or “lion coat”:

Some accounts state that in the battle with the Nemean Lion, “Heracles' armor was, in fact, the hide of the Lion of Cithaeron,” implying that Heracles had previously defeated another Lawagetas, stripped him of his “lion coat” armor, and later wore it to battle the Nemean. After killing the Nemean Lawagetas, Heracles stripped and wore the Nemean’s “lion coat” too. Maybe Heracles’ permanent association with lions and wearing lion-skins came from a reputation for stripping off and wearing the armor of his slain Lawagetas opponents.

Review

Archaeologist Jorrit Kelder notes in The Kingdom of Mycenae that the current consensus on the etymology of Mycenaean Greek title 𐀨𐀷𐀐𐀲 (Lāwāgetās) is without direct evidence connecting it to the Ancient Greek λαός (laós) “people, people assembled, soldiers, common people.” Additionally, the Lawagetas’ roles were more than martial, and could mirror duties of the Wanax, the traveling overlord.

This post speculates that:

Mycenaean title 𐀨𐀷𐀐𐀲 Lawagetas is from 𐀨𐀷 *Lawa “Lion” and 𐀐𐀲 (-getās) “Leader” or “Founder.” Evidence for the meaning of 𐀨𐀷 *Lawa as “lion” is proposed to be in:

Early borrowings of an ancient Mediterranean word for “lion” with a /w/ that was directly borrowed into Proto-West Germanic as *lēwō “lion” and Gothic 𐌻𐌰𐌹𐍅𐌰 (laiwa); these /w/ fingerprints survive into the present as Dutch leeuw “lion” and German Löwe “lion” (similar to /w/ in wīną “wine” from an original Mediterranean word),

Lion iconography at the main entrance to the citadel of Mycenae, and

Consistent Ancient Greek connection of lions with princes and royalty.

𐀨𐀷𐀐𐀲 Lāwāgetās “Lion Leader” was a title and euphemism used for princes of Mycenaean Greece in iconography, similes, and stories. Of all the Mycenaean princes, Heracles was the model Lawagetas. He gained a permanent association with lions and wearing lion-skins from his various princely “Lion Leader” deeds and the wearing of his defeated opponents’ “lion coat” armors, respectively.

Thank you to Jorrit Kelder for his work and scholarship that inspired the speculation in my post.

Thank you for reading.

Nick DeSoto “Dad in SoCal” 23 Aug 2024 @ 1225

A thought on Zeus as the Wanax:

Three instances of Heteropaternal superfecundation (twins born of different fathers) occur with Zeus:

Leda lies with both her husband Tyndareus and with the god Zeus, the latter in the guise of a swan. Nine months later, she bears two daughters: Clytemnestra by Tyndareus and Helen by Zeus.

This happens again; this time Leda bears two sons: Castor by Tyndareus and Pollux by Zeus.

Alcmene lies with Zeus, who is disguised as her husband Amphitryon; Alcmene later lies with the real Amphitryon and gives birth to two sons: Iphicles by Amphitryon and Heracles by Zeus.

If mythology is inspired by history, then these tales could be illustrating a forgotten practice by one or more Wanax that aimed to produce ‘sacred’ twins: royal marriages were consummated by the Wanax and the princely husband, leading to the very rare phenomena of repeated heteropaternal superfecundations among Mycenaean royalty.